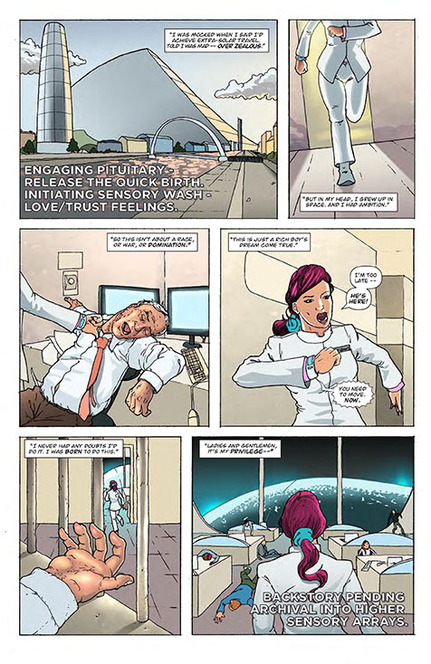

Scottish writer and artist Garry McLaughlin has shown diversity in the industry with a multitude of skills. His latest project Cosmic Gonzo ponders how superheroes effect change of the plane and how their actions are perceived by humanity. Garry recently chatted with comicbookinterviews.com publisher John Michael Helmer about his latest project and his creative career…

JMH: Where were you born and raised?

GARRY: I was born, raised, and still live in Glasgow, Scotland. I've been all over Glasgow and it's surroundings, but I've never lived outside of it for very long. It's always been a really creative place, and while I'd like to live somewhere that has more sunshine, I love it.

JMH: Tell CBI about yourself…

GARRY: I failed art school after one year, and spend nearly a decade doing crappy jobs, becoming pretty dissolute for a while. My "lost years", effectively. I barely picked up a pencil or pen during that time, except to write song lyrics and occasional political rants. It was 2009, roughly ten years after my art school crisis, that I finally started to turn things around and get into art and writing again properly. Since then I've been keeping myself busy, which I think is because I feel like I'm playing catch up, having lost all that time. So in the last five years I've been publishing small press comics, running a community arts charity, forming a small press creators stable called Unthank Comics, and doing art exhibitions and curating for the first time. Basically if someone is willing to let me try something new, I'll do it! I hate being bored, and I like trying out new things, so it works - even if I sometimes feel like I don't know exactly what I'm doing from one day to the next...

JMH: Have you had any formal training in writing?

GARRY: No, my formal writing training lasted only as long as Higher English at Secondary School (or High School, as young 'uns and Americans call it). But it was one of my favorite subjects, and I aced the exams. I've been writing on and off since then - as I said before, I used to write copious amounts of song lyrics, playing with the idea of getting a story or emotion across in few words, and that was a good training for being concise. And I often wrote reports and presentations in jobs I had which was another good education, mainly in how not to bore people! Again, concise transmission of information. Saying only what you need to. Since then it's mainly been practise, getting critique, and watching what the professionals do.

JMH: Who are your writing influences?

GARRY: Without doubt my biggest influence is Grant Morrison. A fellow Glaswegian, the first work of his I read was Arkham Asylum, but the first work I read at an age where I could begin to understand it was The Invisibles. I was already into the occult and magic, and had read Crowley, Peter Carrol, Phil Hine, Robert Anton Wilson. That's kind of how I got to The Invisibles. And it became my bible - it took me a while to work my way through its entirety, and even longer to reach a decent understanding of it, but from volume 1, I realised this was powerful, conscious-raising stuff. That someone could take these magical principles of change, deconstruction, ontological shock, reclamation of the self from the "system", all these big ideas, and write a gutsy spy conspiracy comic around them blew my mind. I've followed his work since, and it's affected (or infected...) my own writing in a big way.

I'm also influenced by Warren Ellis, Alan Moore, the big thinkers of comics. Neil Gaiman's novels and comics, Charles Burns, Kieron Gillen. Outside of comics, I'd say Burroughs, Brion Gysin (The Process is one of the best novels I've ever read), Crowley. I'm a massive fan of Clive Barker, I think there's a lot of folk who aren't aware of the huge scope of his work. And in a non-fiction capacity, Paolo Frere's Pedagogy of the Oppressed was a big influence on Gonzo, although it might not be obvious why for some time.

There seems to be a divide in comics between those who think they're sheer entertainment and those who feel it's an artistic medium, and I think sometimes there's a bit of suspicion of bringing in literary or other influences from outside of the medium. Maybe it's cyclical - the 80s and 90s, in the Vertigo line for example, there was a tonne of that - writers and artists being influenced almost by anything but comics, bringing all this stuff in from the outside. I think that disappeared for a while. Comics are a fantastic indicator of how larger society is functioning, and post 90s there was a reactionary return to big popcorn entertainment and disposable story lines, while also trying to reflect the world outside instead of influencing it - hence terrorism, military-industrial themes, that kind of thing. There's a lot I could say about all that, but I don't want to bore you!

JMH: How did you break into writing comic books?

GARRY: I'm actually a comic artist by trade. I've been penciling comics for five years now, small press stuff mainly. There's a really rich scene in Glasgow, brimming with writers just now, and I had the opportunity to work with some friends who were doing some really interesting stuff. It moved away quite distinctly from underground "comix" to folk pushing the boundaries of what they could achieve in small press. Tackling stuff that stylistically wouldn't be out of place in the majors. But I started out doing seedy, darkly humorous horror comics with Jamie McMorrow, who wrote these beautiful scripts that seemed quite nasty at first but always had this weird emotional core that wrong-footed the reader. He was influenced by Giallo cinema, Hitchcock, all these cinematic and literary influences that I enjoyed myself but had never thought to bring into comics. And I was desperately trying to up my artistic game to keep up with him, but I never really managed it. Our first book, The Abortion, was a silent, black and white comic! The ambition was massive, and I was pushing my own boundaries to try and deliver that stuff. It was a great education - I wasn't dabbling with easy scripts, they were narratively complex. The second, 'Yellow', was told from the perspective of the protagonist, in first person view. These were bold ideas, and I learned a lot in a very short space of time.

Then I started attending the Glasgow League of Writers, mainly because I'd worked with a couple of the guys there, but also because I wanted to get back into writing. I did the art for a one-shot with Stephen Sutherland, Taking Flight, which was my first chance to draw a superhero book, and it was an amazing script. This grounded, realistic super-hero tale which was actually at its heart a kitchen-sink romance between the protagonist and his girlfriend. It was light, breezy and really let me try my hand at the genre I most enjoyed in comics.

During that time, I started messing around with ideas, and all my influences started to come together in Gonzo Cosmic. It took years to write, mainly because I wanted a coherent structure in place that would hold all these big ideas. It started off as something very different from how it turned out - characters and concepts were all ditched in favour of something grander and more sci-fi based, although some of those original ideas will make it into the book at a later stage. Some of the big plot developments later on came from ideas I'd been working on for novels in the preceding years. They changed and developed and found a home in Gonzo. I wanted to do something that was big in scope, but highly compressed, so that readers would be assaulted with ideas that they'd only really understand as the series progressed. Which is a risky strategy, but I felt that because my main work was as an artist, I was free to try and be as bold as possible as a writer. If it doesn't work, I've still got the day job!

Gonzo went through critique at the GLoW group, and folk really liked it - some folk really liked it, there was a big sense of anticipation for it being finally released. That was a boost, knowing that my peers enjoyed it, and could appreciate what it was trying to do. An initial draft had the first story take place over three issues, but advice from Gordon Robertson meant that I decided to compress it even further, and the first two scripts eventually became issue one. That advice re-shaped the book in many ways - in order to compress it I started playing around with the narrative, so that it eventually became that first, looping issue. And the re-draft itself made it into the narrative - when the Cosmic Central Core redacts things in the Discontinuity, that's a reference to the redrafting process. By issue 2, Novak will realize that he experienced the Discontinuity in many different ways, and that's me trying to fold the actual creative process into the narrative, in a way that ties in with ideas I had for later in the book, when things get very... meta.

Comics are a great medium for that kind of play - there are few other experiences we have of sitting there with a visual universe in our hands that we can mess around with time in - novels are constructed to trigger the visuals in the brain - the process of construction happens in one direction only. We rarely flip back through a novel to re-experience something, because we disengage from the process when we do so. But with comics, we can turn a page back to instantly remind ourselves what's happened. Plus they're usually delivered to us in chunks of time, issues, so that we often find ourselves re-reading a previous issue before we come to the next one. That's a fun thing to explore from the perspective of the actual characters, and including the creative process of the book inside itself is too tempting for me to not do it. I can see why comics lend themselves to meta-narrative so easily, and all my favorite books have aspects of that in them. So I'm trying to wear my influences on my sleeve, but also take it in a new direction, if possible. Basically, Gonzo's a manifesto! By issue 12, I want to be able to say, look at what I achieved in a small press, independent book! I hope to grow the readership over the course of the 12 issues, because I think it'll be easier for some people when there are already a bunch of issues out there to catch up on.

JMH: What is the first comic you remember reading?

GARRY: Probably Oor Wullie. D C Thomson used to release these two books, Oor Wullie and The Broons, as annuals, a year about. We'd get one every Christmas, and they were also published as full page strips in The Sunday Post, a really weirdly old-fashioned and parochial Scottish newspaper. Dudley D Watkins wrote and drew them, and they were about a period in Scottish history that had long since gone by the time I was reading them. But there was enough in the characters and stories that I could recognize them - my extended family used to argue over who was which character, and everyone knew who they all were. I've never seen that since with comics - a comic that all the adults and kids read and loved and which was passed from one generation to the next. I wasn't really sure how the strips influenced my own perspective on comics until much later, when I started delivering comic workshops and began deconstructing art and writing for participants. You can look back at those early strips and really see that Watkins was a master at creating a really solid world with fairly basic, black and white drawings. His characters were distinct, their personalities shone through, and the environments were all believable. And all this in a book which almost had a "fixed camera" - most of the panels were medium to long shots which lots of characters in them at one.

Later I got into Frank Quitely's work in a big way, and found his strip from Electric Soup, The Greens, his take on The Broons, and was really excited to see how he'd taken those images in a different direction. It was pretty obvious to me that he was a big fan, and I later found out that Watkins was a big influence on him. That's a Glaswegian thing, I think, or certainly Scottish. Nowhere else had that influence really, although Watkins did do work for The Beano and The Dandy, which traveled a bit further down south to England. Quitely talks about how storytelling is his major driving force when creating comics, and I think that comes from having that early influence of those books - paring things down to the essentials for a Sunday paper, but still being evocative enough to create a whole world. That pretty much sums up Quitely, I think, and it's the reason why he's probably my biggest artistic inspiration.

JMH: Do you read any of the new comic books that are being published today?

GARRY: I go hot and cold with current books, to be honest. I'm a huge X-Men fan, but I feel like it's currently stuck in a bit of a nostalgia trip, bringing back old characters and going over old ground, but I'm kind of biased because my favorite run was Morrison's New X-Men, and I was gutted that the world he left us with, where mutants were taking a dominant role in society and culture, was quickly jettisoned in favour of a return to in-fighting and the old "feared and hated" thing. Conflict in superhero books is so often shown through battle, which is so boring to me. I'd rather we focused on the drama of what it really means to be a mutant, how these weirdoes who are thrown together interact with each other, how they're viewed by the outside world - which, let's face it, would be a complex dynamic. Where are all the people who love mutants and don't want to kill them? Where are the "flatscan" folk signing petitions against mutant oppression and marching en masse to defend them? Where are the mutant feminists, and are they accepted by human feminists - can a mutant ever really be a feminist? Would the queer community expand to encompass mutantkind, or would it be resistant unless those mutants were also queer? And what is queer to mutants?

How would mutants handle foreign affairs between human forces - if they have the power, do they have the right to intervene? Would telepaths not secretly be influencing players on the political stage? Perhaps humans are just pawns in a mutant long game that no one knows about - not in a mutant vs human sense, but in a left versus right, or west versus east sense. For that matter, why do we never properly explore "foreign" attitudes to mutantkind? I'd like to know what it's like for mutants in Iran, and not just broad brushstrokes, but really getting into the lives of Iranian, or Ukranian, or Japanese mutants. What about science - if mutants are at the vanguard of evolution, they should be coming up with incredible new technology, and not just stuff that does more damage. Anyway...

My favorite book of the last year has been Young Avengers, by a longshot. I'm probably not in what would be considered its target demographic, but it was so fresh and unencumbered, and I love Gillen and McKelvie working together. They're a dream team. Marvel Now has been a great success I think, diversifying their art styles and feeling really fresh and poppy again. Daredevil, of course - what a spectacular run on that. Waid and Samnee brought a real energy to the book, and managed to pull off that hardest of tasks - being almost retro but also completely fresh. I think that really made Marvel sit up and take notice of what could be done when you let books breathe, and pair up sympathetic creators. I've enjoyed FF too, but I dig anything Allred does, to be honest.

I'm over events though, I think they're slowly choking the Big Two to death. It seems like every exciting relaunch is quickly lost in the mire of the event story and it just sucks, plain and simple. It's a manipulative marketing ploy to squeeze more money out of an existing readership, and it's myopic, because it really prevents the new influx of readers both companies need.

I tried with the New 52, I really did. As a Marvel boy, it was a great opportunity, a fresh start and bunch of issue 1's to jump on with, but I think they've shown they had no idea what to do beyond that, and it's degenerated into a soup of events, and quickly cancelled books. Sometimes though, I think maybe I'm just getting too old for the superhero books...

Image has been doing really well, they look to me like they know who they are and what they do and have become the place to go for quality material that's not bound by continuity. Infinite Vacation, G0dland, Manhattan Projects, and of course Saga, were all favorites of mine. Saga is sublime - the characterization comes front and centre before the plot, which is amazing considering it's got such a grand scope. Reading Saga, you get the feeling that you're watching a classic unfold before your eyes, and it's been a while since I've felt that.

JMH: Print versus Digital. Your thoughts…

GARRY: I'm a digital convert, or I was until my tablet became irreparably screwed... I don't buy the apocalyptic visions of digital ousting print, not one bit. If anything, I think having those vast libraries available and being able to access books instantly has been a shot in the arm to the industry, and to be honest, retailers are just going to have to work harder to keep up. Walking into most comic shops you're faced with an ocean of books, most of which you can't see the covers for, assembled alphabetically, and rarely by company. Even as someone who's been reading comics for decades, I find them to be exclusive, and not customer friendly. Try walking into the average comic store and browsing to take a chance on some new titles. If you don't already know what you're looking for, it's very difficult. Some stores are excellent, and those are the ones that'll survive, but many of them really need to look at their business model, I think. I realize it's hard for retailers who are stuck in this crazy, monopolized distribution model, and that even affects the decisions the publishers make. It's not easy to diversify, or to streamline the product you hold, when the distributor has such power, but I'd love to see retailers be more clever with merchandising and layout.

My ideal store would have distinct sections for publishers, and even within that, distinct sections for the top tier titles and for new and exciting releases. I think that would make it more welcoming, particularly for the casual or brand new reader. It's like we still buy that whole thing about comics being a genre and not a medium - you'd never walk into a bookstore and just have every book sitting in the shelves in alphabetical order - it would be commercial suicide for a retailer. Why isn't it the same with comics? Digital offers the opportunity to browse at leisure, to search by publisher, genre etc, and the delivery model means that Comixology etc can actively direct customers to editor's picks, Start Here sections and things. That's an interesting approach.

But there will always be room for print, that's never going away. Even if the nature of monthlies changes, people will still always want trades. I'm a sucker for omnibus editions, like the recent Planetary, New X-Men and Invisibles omnibuses. They're great quality, built to last, contain extra material, and look great on the shelf. So I think there's room for both to exist, I think that the only battleground will be the floppies - if retailers and publishers don't work in harmony on this, digital could steal a significant portion of that market away, and that'll force some major changes. Which might leave more room for the indies...

JMH: Writer’s block. How do you get around that creature?

GARRY: I'll cover this in more detail in the question about process, but I rarely sit down to write something without loads of notes and preparatory stuff. For me, it's not conducive to writing to just sit down and write the thing from scratch on a blank page - I've tried it, and it makes writer's block a more common thing. But if I ever do get it, I tend to just go and do something else, like work on some art, play the guitar or just chill for a while. From experience, trying to push through a block is often discouraging, and the best ideas tend to come when you're not fully focusing on the thing. I just let my brain deal with it in the background and do something else.

JMH: What is Gonzo Cosmic?

GARRY: Gonzo Cosmic is a 12 issue series. Broadly it deals with two things - how superheroes could enact actual and total change on the planet, and how that might be perceived by humanity, and also the search for meaning in a world where the rules of the game have already been laid out for you by others. If I had to describe the main theme in one word it would be control.

The first aspect is one that I've been thinking about for a while. Capitalism seems to be struggling - it's a system built on inequality, and also the lie that equality is possible. Desire is supposed to drive people to succeed in a Capitalist economy, but that's really another way of saying it's survival of the fittest, and that's something I have major problems dealing with. But the ideological narrative of the last hundred years has been about the battle between Capitalism and Communism, as if those are the only two options. I've seen few people positing new ideas. I watched the Zeitgeist documentary, which has many detractors, because folk tear into the details to find fault. But I found that it was a consciousness-raising experience - I'd already gone through the deconditioning process of having been brought up in religion, so the first part made perfect sense to me. The parts about our (at the time impending) financial crisis, and the last part about post-scarcity, really made me sit up and take notice.

Capitalism has inherent flaws - the system can reiterate itself to try to cope, but it can never eradicate those flaws, and that's why crisis is seemingly so inherent in our economy. And "scarcity" - the notion that resources are in limited supply - often leads to artificial scarcity in Capitalism. This is when producers suggest that things are in short supply, even though the resources are there to create them in abundance. This means they create desire for them, and can attach a premium price. Think about Apple, hoarding its technology so that it can drip feed new products. They're not really marketing them to new customers, they're encouraging existing customers to trade up. So where we might have bought a phone, for instance, and it would last us a few years before becoming obsolete, now we're encouraged to ditch the last model for the new one once, or even twice a year. Because it's desirable to have the latest one. And that desire comes from marketing, the dark arts of Capitalism.

Once you recognise that, it's not hard to extrapolate out and see how technological advancement is in actual fact held back by the need for profit. It wouldn't do to create a phone that lasts a lifetime in our current economic model - it would be commercial death to the inventor, because the shareholders, who have all the power, would never stand for it.

In the comic, Andel Novak is a billionaire with dreams of going into space - he's the kind of guy who's made his money on artificial scarcity, and he's made it at the expense of workers, the natural world etc. He has an experience where he meets higher dimensional beings who give him power, and the opportunity to see his world in a new light. And so he returns to Earth, determined to change the system. He uses his intelligence to find ways of diminishing scarcity, and his powers to effectively force the ruling classes to go along with him. But how he does so will leave him lots of questions throughout the book, not least of which is, is it right to force change on people just because you have the power to, even if your motives seem pure?

That's a big question which will eventually lead Novak on a different quest. While the world is undergoing these massive changes, he starts to question why these higher dimensional beings have given him this opportunity - there's no such thing as a free lunch, he thinks, which is actually a very Capitalist viewpoint, but he's a child of our era. And he's basically right - the Tertiarists, the beings who transformed him and his crew, have BIG, hidden motives for what they did. So that becomes his goal, to find out why. It's effectively the biggest question of them all, why are we here? Do we have free will?

JMH: Do you research your story ideas? If so, how?

I do, a lot. And particularly for Gonzo. I researched quantum theory, the idea of the multiverse, the nature of time, all that scientific stuff that you'll find throughout the book. I mean, my understanding of science only goes so far - I'm doing the "Cliff Notes" thing a lot of the time, looking at pretty basic ways of understanding this stuff. But even though it's fiction and I take lots of liberties, I'd like the book to at least feel like it's based on something solid, even if I throw that out the window. And I'm trying to do it in a way where I'm not spelling stuff out for the reader. I'd like them to be able to explore further outside of the book if they want to.

I've also been researching conscientisation and critical thinking, something that's discussed in Paulo Frere's 'Pedagogy of the Oppressed'. He talks about the "banking model" of education, where students are perceived as empty vessels to be filled by 'experts'. And he sees this as being a root cause of the dynamic between the oppressed and oppressors in society. The book argues for a more cooperative type of learning, where the student is actively involved in the creation of knowledge. Praxis is basically reflection and action on the world - as I see it, it's the ability to act, and then question why you acted, and what resulted. It's about not just absorbing ideas, but testing them, and then evaluating the results. Frere believed that critical thinking could help people to raise themselves out of being oppressed, but that it required a type of education in which they found the means by which to do it for themselves, rather than being given freedom, or being told how to be free.

That kind of theory is something I've tried to apply in the community art workshops I do - I try not to act as the "expert", but encourage participants to do things, and then explore what they've done. And with Gonzo, the theory is there in the narrative, in the sense that the characters have to go through their own journey of becoming "conscious" thinkers, but also butting up against the structures that are in place to control their consciousness, or their ability to act on it. And I'm trying to bring the readers along on that journey too - as I said earlier, I don't want to tell the readers everything they need to know, I want them to think it through for themselves, and come up with their own answers. That's a tricky strategy in my first indie book! We're often used to being passive recipients of entertainment. But it can be done - The Invisibles is all about that, if you ask me. That final line - "See, now! Our sentence is up!" - that has double and triple meanings that can only be decoded by active involvement on the readers' behalf. Is it just another way of saying "The End"? Is it a call to arms? Or is it asking us to look at how the characters in the book have ostensibly found a way to navigate themselves off the page and into our heads, as a metaphor for how we might be able to do the same with the structures of control in our own lives? It's all of these things, and more, and every reader will interpret it differently. But critical thinking would suggest that we look for all of those meanings, not just the one that we're immediately conditioned to experience or recognise. I still don't necessarily think The Invisibles gets the full credit it deserves for that - it's basically the only comic book I've read that is so bold about its aims. For me, it was a call to arms, to become Invisible. And becoming Invisible means taking those ideas and propagating them further, spreading the word of change and liberation. Resisting the attempts of the society around you to write your narrative. Taking back control.

JMH: What is your writing process like?

GARRY: I write 90% in my head. It's the only way to do it. Like I said earlier, sitting down at a blank page or screen to go, Page 1 Panel 1, doesn't work for me. I make notes about my initial ideas, then I let them swim in my head. Once I've got the basic structure in my mind, I'll write that down - here's the long arc, here's the shorter arcs, major plot points, where the characters should be. Then I let each scene swim. I let the characters act out things before they ever get on the page. Sometimes a full scene will come to me whole, and I'll write it down in a notebook. Often conversations will appear in my head, and they drive a scene forward.

Then I'll do a breakdown for the issue I'm writing. I list all the pages and write down the major plot and action beats for each. That means that when I come to write it, it's a matter of gathering together my notes, and tying them up to the structure. That's not fixed, by the way. As I'm writing, I'll swap things around, make certain scenes longer, and jettison stuff that's no longer useful. But I'll get the first draft down, which tends to be pretty fully formed by this point. Then I'll get feedback and critique from folk I know, and I'll redraft it. I'm still refining it, the first scripts for Gonzo went through a lot of changes, and still are. But I feel like from issue 4 onwards, the process will be a lot tighter. I've been living with the series for about 2 years now, I've got scenes written for later issues, and I've actually got the end of the whole book written down somewhere! So it's a matter of drawing all that together, and making sure it's consistent and stands up on its own. Issues 2 and 3 complete a short arc, but by issue 4 I feel like readers will know much more about these characters and the world they live in, so I can really get into the meat of the story.

JMH: Do your stories carry a message?

GARRY: Yes! I think that all stories should have a message of some kind, otherwise what's the point? Even if that message is something kind of architectural about the medium - like, let's explore the best way to write a superhero book, you know? It doesn't have to be big or profound. But I've got a lot of things that bug or interest me, and those are things I want to share. Inequality, control, oppression, the nature of being, physics etc. They're big things, and they certainly come across as big in Gonzo, but I've got ideas for exploring them in much "smaller" work too. It's not always going to be a polemic...

JMH: Do you feel more comfortable with writing prose or comic book sequential storytelling?

GARRY: Definitely sequential. I tried my hand at prose when I was younger, and I wrote a novel that I self-published on a limited basis (which always feels more like vanity publishing than small press comics do - I don't know why that is...). But I never really got to grips with it - too many ideas, not enough structure, that kind of thing. Maybe because I'm also an artist, sequential work feels much more natural. Writing for art works for me - I know that there's more to it than having my words carry everything in the story. I wrote Gonzo knowing I would draw it, but I tried to write the script fully as if it was another artist working on it, because I wanted the practice, but also because I felt like taking shortcuts would change the work, and when I came to draw it, I'd still be redrafting. I wanted to write the book as close to the finished page as I could.

JMH: What future projects are in the works?

GARRY: Gonzo is probably going to take me four years to complete, so my ability to do other writing stuff is limited, although I've written the first draft of a timey-wimey one-shot called Recursion, that I'd like to polish and get an artist on board for, just so that I'm not consumed by Gonzo. But I've started a small press label called Unthank Comics, and I'm doing art on a book just now called Freak Out Squares by a fantastic writer called Harry French. There's some similarities in the themes - he's dealing with the broad theme of control too, I guess, and it's nice to be working on something that doesn't feel too far from Gonzo. And the art for Gonzo is taking up the rest of my time - I've started issue 2, and I hope to have it out by the end of April, beginning of May. That might slip a bit, but my aim is to get three issues out this year.

JMH: Where can fans get a hold of your books?

GARRY: The easiest way to get hold of it is to go the website, www.unthankcomics.co.uk. Digital and print versions available. It's going to Comixology Submit, hopefully, as soon as I iron out some kinks.

JMH: How can fans and publishers contact you?

GARRY: Email me! [email protected] is the best address to use. I'm keen to hear what readers think of the book - it's a dialogue, and I've got the luxury of being able to mould it over the course of the series, something I wouldn't be able to do so well if it was coming out monthly.

JMH: Anything else you'd like to mention that we haven't covered yet?

GARRY: I think I've rambled for long enough!

JMH: Garry, CBI appreciates your time! All the best!

GARRY: Thanks John, it's been great! Nice to get the opportunity to talk in-depth about Gonzo!

JMH: Where were you born and raised?

GARRY: I was born, raised, and still live in Glasgow, Scotland. I've been all over Glasgow and it's surroundings, but I've never lived outside of it for very long. It's always been a really creative place, and while I'd like to live somewhere that has more sunshine, I love it.

JMH: Tell CBI about yourself…

GARRY: I failed art school after one year, and spend nearly a decade doing crappy jobs, becoming pretty dissolute for a while. My "lost years", effectively. I barely picked up a pencil or pen during that time, except to write song lyrics and occasional political rants. It was 2009, roughly ten years after my art school crisis, that I finally started to turn things around and get into art and writing again properly. Since then I've been keeping myself busy, which I think is because I feel like I'm playing catch up, having lost all that time. So in the last five years I've been publishing small press comics, running a community arts charity, forming a small press creators stable called Unthank Comics, and doing art exhibitions and curating for the first time. Basically if someone is willing to let me try something new, I'll do it! I hate being bored, and I like trying out new things, so it works - even if I sometimes feel like I don't know exactly what I'm doing from one day to the next...

JMH: Have you had any formal training in writing?

GARRY: No, my formal writing training lasted only as long as Higher English at Secondary School (or High School, as young 'uns and Americans call it). But it was one of my favorite subjects, and I aced the exams. I've been writing on and off since then - as I said before, I used to write copious amounts of song lyrics, playing with the idea of getting a story or emotion across in few words, and that was a good training for being concise. And I often wrote reports and presentations in jobs I had which was another good education, mainly in how not to bore people! Again, concise transmission of information. Saying only what you need to. Since then it's mainly been practise, getting critique, and watching what the professionals do.

JMH: Who are your writing influences?

GARRY: Without doubt my biggest influence is Grant Morrison. A fellow Glaswegian, the first work of his I read was Arkham Asylum, but the first work I read at an age where I could begin to understand it was The Invisibles. I was already into the occult and magic, and had read Crowley, Peter Carrol, Phil Hine, Robert Anton Wilson. That's kind of how I got to The Invisibles. And it became my bible - it took me a while to work my way through its entirety, and even longer to reach a decent understanding of it, but from volume 1, I realised this was powerful, conscious-raising stuff. That someone could take these magical principles of change, deconstruction, ontological shock, reclamation of the self from the "system", all these big ideas, and write a gutsy spy conspiracy comic around them blew my mind. I've followed his work since, and it's affected (or infected...) my own writing in a big way.

I'm also influenced by Warren Ellis, Alan Moore, the big thinkers of comics. Neil Gaiman's novels and comics, Charles Burns, Kieron Gillen. Outside of comics, I'd say Burroughs, Brion Gysin (The Process is one of the best novels I've ever read), Crowley. I'm a massive fan of Clive Barker, I think there's a lot of folk who aren't aware of the huge scope of his work. And in a non-fiction capacity, Paolo Frere's Pedagogy of the Oppressed was a big influence on Gonzo, although it might not be obvious why for some time.

There seems to be a divide in comics between those who think they're sheer entertainment and those who feel it's an artistic medium, and I think sometimes there's a bit of suspicion of bringing in literary or other influences from outside of the medium. Maybe it's cyclical - the 80s and 90s, in the Vertigo line for example, there was a tonne of that - writers and artists being influenced almost by anything but comics, bringing all this stuff in from the outside. I think that disappeared for a while. Comics are a fantastic indicator of how larger society is functioning, and post 90s there was a reactionary return to big popcorn entertainment and disposable story lines, while also trying to reflect the world outside instead of influencing it - hence terrorism, military-industrial themes, that kind of thing. There's a lot I could say about all that, but I don't want to bore you!

JMH: How did you break into writing comic books?

GARRY: I'm actually a comic artist by trade. I've been penciling comics for five years now, small press stuff mainly. There's a really rich scene in Glasgow, brimming with writers just now, and I had the opportunity to work with some friends who were doing some really interesting stuff. It moved away quite distinctly from underground "comix" to folk pushing the boundaries of what they could achieve in small press. Tackling stuff that stylistically wouldn't be out of place in the majors. But I started out doing seedy, darkly humorous horror comics with Jamie McMorrow, who wrote these beautiful scripts that seemed quite nasty at first but always had this weird emotional core that wrong-footed the reader. He was influenced by Giallo cinema, Hitchcock, all these cinematic and literary influences that I enjoyed myself but had never thought to bring into comics. And I was desperately trying to up my artistic game to keep up with him, but I never really managed it. Our first book, The Abortion, was a silent, black and white comic! The ambition was massive, and I was pushing my own boundaries to try and deliver that stuff. It was a great education - I wasn't dabbling with easy scripts, they were narratively complex. The second, 'Yellow', was told from the perspective of the protagonist, in first person view. These were bold ideas, and I learned a lot in a very short space of time.

Then I started attending the Glasgow League of Writers, mainly because I'd worked with a couple of the guys there, but also because I wanted to get back into writing. I did the art for a one-shot with Stephen Sutherland, Taking Flight, which was my first chance to draw a superhero book, and it was an amazing script. This grounded, realistic super-hero tale which was actually at its heart a kitchen-sink romance between the protagonist and his girlfriend. It was light, breezy and really let me try my hand at the genre I most enjoyed in comics.

During that time, I started messing around with ideas, and all my influences started to come together in Gonzo Cosmic. It took years to write, mainly because I wanted a coherent structure in place that would hold all these big ideas. It started off as something very different from how it turned out - characters and concepts were all ditched in favour of something grander and more sci-fi based, although some of those original ideas will make it into the book at a later stage. Some of the big plot developments later on came from ideas I'd been working on for novels in the preceding years. They changed and developed and found a home in Gonzo. I wanted to do something that was big in scope, but highly compressed, so that readers would be assaulted with ideas that they'd only really understand as the series progressed. Which is a risky strategy, but I felt that because my main work was as an artist, I was free to try and be as bold as possible as a writer. If it doesn't work, I've still got the day job!

Gonzo went through critique at the GLoW group, and folk really liked it - some folk really liked it, there was a big sense of anticipation for it being finally released. That was a boost, knowing that my peers enjoyed it, and could appreciate what it was trying to do. An initial draft had the first story take place over three issues, but advice from Gordon Robertson meant that I decided to compress it even further, and the first two scripts eventually became issue one. That advice re-shaped the book in many ways - in order to compress it I started playing around with the narrative, so that it eventually became that first, looping issue. And the re-draft itself made it into the narrative - when the Cosmic Central Core redacts things in the Discontinuity, that's a reference to the redrafting process. By issue 2, Novak will realize that he experienced the Discontinuity in many different ways, and that's me trying to fold the actual creative process into the narrative, in a way that ties in with ideas I had for later in the book, when things get very... meta.

Comics are a great medium for that kind of play - there are few other experiences we have of sitting there with a visual universe in our hands that we can mess around with time in - novels are constructed to trigger the visuals in the brain - the process of construction happens in one direction only. We rarely flip back through a novel to re-experience something, because we disengage from the process when we do so. But with comics, we can turn a page back to instantly remind ourselves what's happened. Plus they're usually delivered to us in chunks of time, issues, so that we often find ourselves re-reading a previous issue before we come to the next one. That's a fun thing to explore from the perspective of the actual characters, and including the creative process of the book inside itself is too tempting for me to not do it. I can see why comics lend themselves to meta-narrative so easily, and all my favorite books have aspects of that in them. So I'm trying to wear my influences on my sleeve, but also take it in a new direction, if possible. Basically, Gonzo's a manifesto! By issue 12, I want to be able to say, look at what I achieved in a small press, independent book! I hope to grow the readership over the course of the 12 issues, because I think it'll be easier for some people when there are already a bunch of issues out there to catch up on.

JMH: What is the first comic you remember reading?

GARRY: Probably Oor Wullie. D C Thomson used to release these two books, Oor Wullie and The Broons, as annuals, a year about. We'd get one every Christmas, and they were also published as full page strips in The Sunday Post, a really weirdly old-fashioned and parochial Scottish newspaper. Dudley D Watkins wrote and drew them, and they were about a period in Scottish history that had long since gone by the time I was reading them. But there was enough in the characters and stories that I could recognize them - my extended family used to argue over who was which character, and everyone knew who they all were. I've never seen that since with comics - a comic that all the adults and kids read and loved and which was passed from one generation to the next. I wasn't really sure how the strips influenced my own perspective on comics until much later, when I started delivering comic workshops and began deconstructing art and writing for participants. You can look back at those early strips and really see that Watkins was a master at creating a really solid world with fairly basic, black and white drawings. His characters were distinct, their personalities shone through, and the environments were all believable. And all this in a book which almost had a "fixed camera" - most of the panels were medium to long shots which lots of characters in them at one.

Later I got into Frank Quitely's work in a big way, and found his strip from Electric Soup, The Greens, his take on The Broons, and was really excited to see how he'd taken those images in a different direction. It was pretty obvious to me that he was a big fan, and I later found out that Watkins was a big influence on him. That's a Glaswegian thing, I think, or certainly Scottish. Nowhere else had that influence really, although Watkins did do work for The Beano and The Dandy, which traveled a bit further down south to England. Quitely talks about how storytelling is his major driving force when creating comics, and I think that comes from having that early influence of those books - paring things down to the essentials for a Sunday paper, but still being evocative enough to create a whole world. That pretty much sums up Quitely, I think, and it's the reason why he's probably my biggest artistic inspiration.

JMH: Do you read any of the new comic books that are being published today?

GARRY: I go hot and cold with current books, to be honest. I'm a huge X-Men fan, but I feel like it's currently stuck in a bit of a nostalgia trip, bringing back old characters and going over old ground, but I'm kind of biased because my favorite run was Morrison's New X-Men, and I was gutted that the world he left us with, where mutants were taking a dominant role in society and culture, was quickly jettisoned in favour of a return to in-fighting and the old "feared and hated" thing. Conflict in superhero books is so often shown through battle, which is so boring to me. I'd rather we focused on the drama of what it really means to be a mutant, how these weirdoes who are thrown together interact with each other, how they're viewed by the outside world - which, let's face it, would be a complex dynamic. Where are all the people who love mutants and don't want to kill them? Where are the "flatscan" folk signing petitions against mutant oppression and marching en masse to defend them? Where are the mutant feminists, and are they accepted by human feminists - can a mutant ever really be a feminist? Would the queer community expand to encompass mutantkind, or would it be resistant unless those mutants were also queer? And what is queer to mutants?

How would mutants handle foreign affairs between human forces - if they have the power, do they have the right to intervene? Would telepaths not secretly be influencing players on the political stage? Perhaps humans are just pawns in a mutant long game that no one knows about - not in a mutant vs human sense, but in a left versus right, or west versus east sense. For that matter, why do we never properly explore "foreign" attitudes to mutantkind? I'd like to know what it's like for mutants in Iran, and not just broad brushstrokes, but really getting into the lives of Iranian, or Ukranian, or Japanese mutants. What about science - if mutants are at the vanguard of evolution, they should be coming up with incredible new technology, and not just stuff that does more damage. Anyway...

My favorite book of the last year has been Young Avengers, by a longshot. I'm probably not in what would be considered its target demographic, but it was so fresh and unencumbered, and I love Gillen and McKelvie working together. They're a dream team. Marvel Now has been a great success I think, diversifying their art styles and feeling really fresh and poppy again. Daredevil, of course - what a spectacular run on that. Waid and Samnee brought a real energy to the book, and managed to pull off that hardest of tasks - being almost retro but also completely fresh. I think that really made Marvel sit up and take notice of what could be done when you let books breathe, and pair up sympathetic creators. I've enjoyed FF too, but I dig anything Allred does, to be honest.

I'm over events though, I think they're slowly choking the Big Two to death. It seems like every exciting relaunch is quickly lost in the mire of the event story and it just sucks, plain and simple. It's a manipulative marketing ploy to squeeze more money out of an existing readership, and it's myopic, because it really prevents the new influx of readers both companies need.

I tried with the New 52, I really did. As a Marvel boy, it was a great opportunity, a fresh start and bunch of issue 1's to jump on with, but I think they've shown they had no idea what to do beyond that, and it's degenerated into a soup of events, and quickly cancelled books. Sometimes though, I think maybe I'm just getting too old for the superhero books...

Image has been doing really well, they look to me like they know who they are and what they do and have become the place to go for quality material that's not bound by continuity. Infinite Vacation, G0dland, Manhattan Projects, and of course Saga, were all favorites of mine. Saga is sublime - the characterization comes front and centre before the plot, which is amazing considering it's got such a grand scope. Reading Saga, you get the feeling that you're watching a classic unfold before your eyes, and it's been a while since I've felt that.

JMH: Print versus Digital. Your thoughts…

GARRY: I'm a digital convert, or I was until my tablet became irreparably screwed... I don't buy the apocalyptic visions of digital ousting print, not one bit. If anything, I think having those vast libraries available and being able to access books instantly has been a shot in the arm to the industry, and to be honest, retailers are just going to have to work harder to keep up. Walking into most comic shops you're faced with an ocean of books, most of which you can't see the covers for, assembled alphabetically, and rarely by company. Even as someone who's been reading comics for decades, I find them to be exclusive, and not customer friendly. Try walking into the average comic store and browsing to take a chance on some new titles. If you don't already know what you're looking for, it's very difficult. Some stores are excellent, and those are the ones that'll survive, but many of them really need to look at their business model, I think. I realize it's hard for retailers who are stuck in this crazy, monopolized distribution model, and that even affects the decisions the publishers make. It's not easy to diversify, or to streamline the product you hold, when the distributor has such power, but I'd love to see retailers be more clever with merchandising and layout.

My ideal store would have distinct sections for publishers, and even within that, distinct sections for the top tier titles and for new and exciting releases. I think that would make it more welcoming, particularly for the casual or brand new reader. It's like we still buy that whole thing about comics being a genre and not a medium - you'd never walk into a bookstore and just have every book sitting in the shelves in alphabetical order - it would be commercial suicide for a retailer. Why isn't it the same with comics? Digital offers the opportunity to browse at leisure, to search by publisher, genre etc, and the delivery model means that Comixology etc can actively direct customers to editor's picks, Start Here sections and things. That's an interesting approach.

But there will always be room for print, that's never going away. Even if the nature of monthlies changes, people will still always want trades. I'm a sucker for omnibus editions, like the recent Planetary, New X-Men and Invisibles omnibuses. They're great quality, built to last, contain extra material, and look great on the shelf. So I think there's room for both to exist, I think that the only battleground will be the floppies - if retailers and publishers don't work in harmony on this, digital could steal a significant portion of that market away, and that'll force some major changes. Which might leave more room for the indies...

JMH: Writer’s block. How do you get around that creature?

GARRY: I'll cover this in more detail in the question about process, but I rarely sit down to write something without loads of notes and preparatory stuff. For me, it's not conducive to writing to just sit down and write the thing from scratch on a blank page - I've tried it, and it makes writer's block a more common thing. But if I ever do get it, I tend to just go and do something else, like work on some art, play the guitar or just chill for a while. From experience, trying to push through a block is often discouraging, and the best ideas tend to come when you're not fully focusing on the thing. I just let my brain deal with it in the background and do something else.

JMH: What is Gonzo Cosmic?

GARRY: Gonzo Cosmic is a 12 issue series. Broadly it deals with two things - how superheroes could enact actual and total change on the planet, and how that might be perceived by humanity, and also the search for meaning in a world where the rules of the game have already been laid out for you by others. If I had to describe the main theme in one word it would be control.

The first aspect is one that I've been thinking about for a while. Capitalism seems to be struggling - it's a system built on inequality, and also the lie that equality is possible. Desire is supposed to drive people to succeed in a Capitalist economy, but that's really another way of saying it's survival of the fittest, and that's something I have major problems dealing with. But the ideological narrative of the last hundred years has been about the battle between Capitalism and Communism, as if those are the only two options. I've seen few people positing new ideas. I watched the Zeitgeist documentary, which has many detractors, because folk tear into the details to find fault. But I found that it was a consciousness-raising experience - I'd already gone through the deconditioning process of having been brought up in religion, so the first part made perfect sense to me. The parts about our (at the time impending) financial crisis, and the last part about post-scarcity, really made me sit up and take notice.

Capitalism has inherent flaws - the system can reiterate itself to try to cope, but it can never eradicate those flaws, and that's why crisis is seemingly so inherent in our economy. And "scarcity" - the notion that resources are in limited supply - often leads to artificial scarcity in Capitalism. This is when producers suggest that things are in short supply, even though the resources are there to create them in abundance. This means they create desire for them, and can attach a premium price. Think about Apple, hoarding its technology so that it can drip feed new products. They're not really marketing them to new customers, they're encouraging existing customers to trade up. So where we might have bought a phone, for instance, and it would last us a few years before becoming obsolete, now we're encouraged to ditch the last model for the new one once, or even twice a year. Because it's desirable to have the latest one. And that desire comes from marketing, the dark arts of Capitalism.

Once you recognise that, it's not hard to extrapolate out and see how technological advancement is in actual fact held back by the need for profit. It wouldn't do to create a phone that lasts a lifetime in our current economic model - it would be commercial death to the inventor, because the shareholders, who have all the power, would never stand for it.

In the comic, Andel Novak is a billionaire with dreams of going into space - he's the kind of guy who's made his money on artificial scarcity, and he's made it at the expense of workers, the natural world etc. He has an experience where he meets higher dimensional beings who give him power, and the opportunity to see his world in a new light. And so he returns to Earth, determined to change the system. He uses his intelligence to find ways of diminishing scarcity, and his powers to effectively force the ruling classes to go along with him. But how he does so will leave him lots of questions throughout the book, not least of which is, is it right to force change on people just because you have the power to, even if your motives seem pure?

That's a big question which will eventually lead Novak on a different quest. While the world is undergoing these massive changes, he starts to question why these higher dimensional beings have given him this opportunity - there's no such thing as a free lunch, he thinks, which is actually a very Capitalist viewpoint, but he's a child of our era. And he's basically right - the Tertiarists, the beings who transformed him and his crew, have BIG, hidden motives for what they did. So that becomes his goal, to find out why. It's effectively the biggest question of them all, why are we here? Do we have free will?

JMH: Do you research your story ideas? If so, how?

I do, a lot. And particularly for Gonzo. I researched quantum theory, the idea of the multiverse, the nature of time, all that scientific stuff that you'll find throughout the book. I mean, my understanding of science only goes so far - I'm doing the "Cliff Notes" thing a lot of the time, looking at pretty basic ways of understanding this stuff. But even though it's fiction and I take lots of liberties, I'd like the book to at least feel like it's based on something solid, even if I throw that out the window. And I'm trying to do it in a way where I'm not spelling stuff out for the reader. I'd like them to be able to explore further outside of the book if they want to.

I've also been researching conscientisation and critical thinking, something that's discussed in Paulo Frere's 'Pedagogy of the Oppressed'. He talks about the "banking model" of education, where students are perceived as empty vessels to be filled by 'experts'. And he sees this as being a root cause of the dynamic between the oppressed and oppressors in society. The book argues for a more cooperative type of learning, where the student is actively involved in the creation of knowledge. Praxis is basically reflection and action on the world - as I see it, it's the ability to act, and then question why you acted, and what resulted. It's about not just absorbing ideas, but testing them, and then evaluating the results. Frere believed that critical thinking could help people to raise themselves out of being oppressed, but that it required a type of education in which they found the means by which to do it for themselves, rather than being given freedom, or being told how to be free.

That kind of theory is something I've tried to apply in the community art workshops I do - I try not to act as the "expert", but encourage participants to do things, and then explore what they've done. And with Gonzo, the theory is there in the narrative, in the sense that the characters have to go through their own journey of becoming "conscious" thinkers, but also butting up against the structures that are in place to control their consciousness, or their ability to act on it. And I'm trying to bring the readers along on that journey too - as I said earlier, I don't want to tell the readers everything they need to know, I want them to think it through for themselves, and come up with their own answers. That's a tricky strategy in my first indie book! We're often used to being passive recipients of entertainment. But it can be done - The Invisibles is all about that, if you ask me. That final line - "See, now! Our sentence is up!" - that has double and triple meanings that can only be decoded by active involvement on the readers' behalf. Is it just another way of saying "The End"? Is it a call to arms? Or is it asking us to look at how the characters in the book have ostensibly found a way to navigate themselves off the page and into our heads, as a metaphor for how we might be able to do the same with the structures of control in our own lives? It's all of these things, and more, and every reader will interpret it differently. But critical thinking would suggest that we look for all of those meanings, not just the one that we're immediately conditioned to experience or recognise. I still don't necessarily think The Invisibles gets the full credit it deserves for that - it's basically the only comic book I've read that is so bold about its aims. For me, it was a call to arms, to become Invisible. And becoming Invisible means taking those ideas and propagating them further, spreading the word of change and liberation. Resisting the attempts of the society around you to write your narrative. Taking back control.

JMH: What is your writing process like?

GARRY: I write 90% in my head. It's the only way to do it. Like I said earlier, sitting down at a blank page or screen to go, Page 1 Panel 1, doesn't work for me. I make notes about my initial ideas, then I let them swim in my head. Once I've got the basic structure in my mind, I'll write that down - here's the long arc, here's the shorter arcs, major plot points, where the characters should be. Then I let each scene swim. I let the characters act out things before they ever get on the page. Sometimes a full scene will come to me whole, and I'll write it down in a notebook. Often conversations will appear in my head, and they drive a scene forward.

Then I'll do a breakdown for the issue I'm writing. I list all the pages and write down the major plot and action beats for each. That means that when I come to write it, it's a matter of gathering together my notes, and tying them up to the structure. That's not fixed, by the way. As I'm writing, I'll swap things around, make certain scenes longer, and jettison stuff that's no longer useful. But I'll get the first draft down, which tends to be pretty fully formed by this point. Then I'll get feedback and critique from folk I know, and I'll redraft it. I'm still refining it, the first scripts for Gonzo went through a lot of changes, and still are. But I feel like from issue 4 onwards, the process will be a lot tighter. I've been living with the series for about 2 years now, I've got scenes written for later issues, and I've actually got the end of the whole book written down somewhere! So it's a matter of drawing all that together, and making sure it's consistent and stands up on its own. Issues 2 and 3 complete a short arc, but by issue 4 I feel like readers will know much more about these characters and the world they live in, so I can really get into the meat of the story.

JMH: Do your stories carry a message?

GARRY: Yes! I think that all stories should have a message of some kind, otherwise what's the point? Even if that message is something kind of architectural about the medium - like, let's explore the best way to write a superhero book, you know? It doesn't have to be big or profound. But I've got a lot of things that bug or interest me, and those are things I want to share. Inequality, control, oppression, the nature of being, physics etc. They're big things, and they certainly come across as big in Gonzo, but I've got ideas for exploring them in much "smaller" work too. It's not always going to be a polemic...

JMH: Do you feel more comfortable with writing prose or comic book sequential storytelling?

GARRY: Definitely sequential. I tried my hand at prose when I was younger, and I wrote a novel that I self-published on a limited basis (which always feels more like vanity publishing than small press comics do - I don't know why that is...). But I never really got to grips with it - too many ideas, not enough structure, that kind of thing. Maybe because I'm also an artist, sequential work feels much more natural. Writing for art works for me - I know that there's more to it than having my words carry everything in the story. I wrote Gonzo knowing I would draw it, but I tried to write the script fully as if it was another artist working on it, because I wanted the practice, but also because I felt like taking shortcuts would change the work, and when I came to draw it, I'd still be redrafting. I wanted to write the book as close to the finished page as I could.

JMH: What future projects are in the works?

GARRY: Gonzo is probably going to take me four years to complete, so my ability to do other writing stuff is limited, although I've written the first draft of a timey-wimey one-shot called Recursion, that I'd like to polish and get an artist on board for, just so that I'm not consumed by Gonzo. But I've started a small press label called Unthank Comics, and I'm doing art on a book just now called Freak Out Squares by a fantastic writer called Harry French. There's some similarities in the themes - he's dealing with the broad theme of control too, I guess, and it's nice to be working on something that doesn't feel too far from Gonzo. And the art for Gonzo is taking up the rest of my time - I've started issue 2, and I hope to have it out by the end of April, beginning of May. That might slip a bit, but my aim is to get three issues out this year.

JMH: Where can fans get a hold of your books?

GARRY: The easiest way to get hold of it is to go the website, www.unthankcomics.co.uk. Digital and print versions available. It's going to Comixology Submit, hopefully, as soon as I iron out some kinks.

JMH: How can fans and publishers contact you?

GARRY: Email me! [email protected] is the best address to use. I'm keen to hear what readers think of the book - it's a dialogue, and I've got the luxury of being able to mould it over the course of the series, something I wouldn't be able to do so well if it was coming out monthly.

JMH: Anything else you'd like to mention that we haven't covered yet?

GARRY: I think I've rambled for long enough!

JMH: Garry, CBI appreciates your time! All the best!

GARRY: Thanks John, it's been great! Nice to get the opportunity to talk in-depth about Gonzo!

All interviews on this website © 2011-2022 Comicbookinterviews.com